Garfield update 2009-2010

1. No governmental relief is in sight for homeowners except in isolated instances of community action together with publicity from the media.

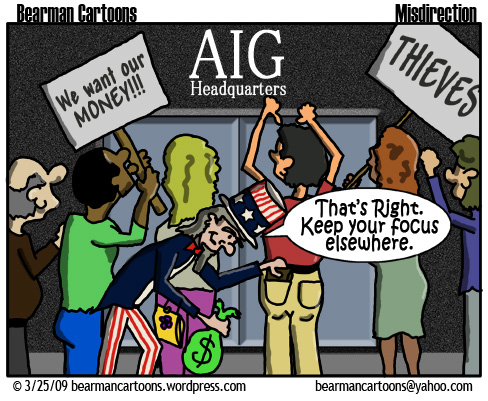

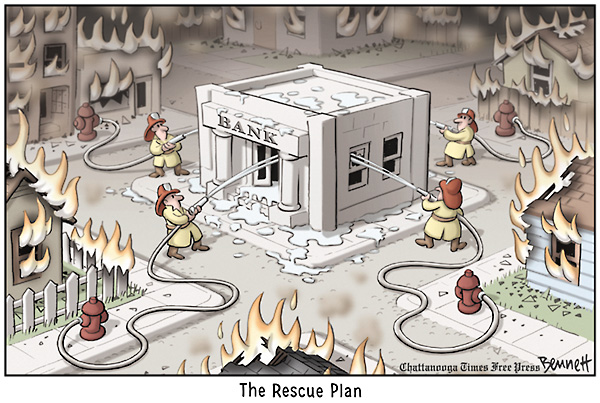

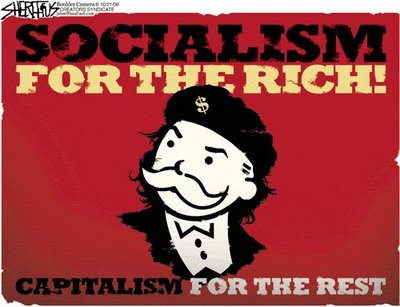

2. State and federal governments continue to sink deeper into debt, cutting social and necessary services while avoiding the elephant in the living room: the trillions of dollars owed and collectible in taxes, recording fees, filing fees, late fees, penalties, financial damages, punitive damages and interest due from the intermediary players on Wall Street who created trading “instruments” based upon conveyance of interests in real property located within state borders. The death grip of the lobby for the financial service industry is likely to continue thus making it impossible to resolve the housing crisis, the state budget crisis or the federal budget deficit.

3. Using taxpayer funds borrowed from foreign governments or created through quantitative easing, trillions of dollars have been paid, or provided in “credit lines” to intermediaries on the false premise that they own or control the mortgage backed securities that have defaulted. Foreclosures continue to hit new highs. Total money injected into the system exceeds 8 trillion dollars. Record profits announced by the financial services industry in which power is now more concentrated than before, making them the strongest influence in Federal and State capitals around the world.

4. Toxic Titles reveal unmarketable properties in and out of foreclosures with no relief in sight because nearly everyone is ignoring this basic problem that is a deal-breaker on every transfer of an interest in real property.

5. Evictions continue to hit new highs as Judges continue to be bombarded with ill-conceived motions that do not address the jurisdiction or authority of the court. The illegal evictions are based upon fraudulent conveyances procured through abuse of the foreclosure process and direct misrepresentations and fraud upon the court and recording system in each county as to the documents fabricated for purposes of foreclosure — creating the illusion of a proper paper trail.

6. 1.7 million new foreclosed properties are due to hit the market according to published statistics. Livinglies estimate the number to be at least 4 million.

7. Downward pressure on both price and marketability continues with no end in sight.

8. Unemployment continues to rise, albeit far more slowly than at the beginning of 2009. Unemployment, underemployment, employment drop-outs, absence of entry-level jobs, low statistics on new business starts, and former members of workforce (particularly men) are harbingers for continued decline in median income combined with higher expenses for key components, particularly health care. The ability to pay anything other than rent is continuing its decline.

9. Concurrent with the increase in foreclosures and the decrease in housing prices, official figures put the number of homes underwater at 25%. Livinglies estimates that when you look at three components not included in official statistics, the figure rises to more than 45%. The components are selling discounts, selling expenses, and continued delusional asking prices that will soon crash when sellers realize that past high prices were an illusion, not a market fluctuation.

10. The number of people walking from their homes is increasing daily, including people who are not behind in their mortgages. This is increasing the inventory of homes that are not officially included in the pipeline because they are not sufficiently advanced in the delinquency or foreclosure process. This is a hidden second wave of pressure on housing prices and marketability.

11. With the entire economy on government life-support that is not completely effective in preventing rises in homelessness and people requiring public assistance, the likelihood of severe social unrest and political upheaval increases month by month. Increasing risks of unrest prompted at least one Wall Street Bank to order enough firearms and ammunition to start an armory.

12. Modification of mortgages has been largely a sham.

13. Short-sales have been largely a sham.

14. Quiet titles in favor of homeowners are increasing at a slow pace as the sophistication of defenses improves on the side of financial services companies seeking free homes through foreclosures.

15. Legislative Intervention has been ineffective and indeed, misleading

16. Executive intervention has been virtually non-existent. The people who perpetrated this fraud not only have evaded prosecution, they maintain close relationships with the Obama administration.

17. Judicial intervention has been spotty and could be much better once people accept the complexity of securitization and the simplicity of STRATEGIES THAT WORK.

18. Legal profession , slow to start went from zero to 15 mph during 2009. Let’s hope they get to 60 mph during 2010.

19. Accounting profession, which has thus far stayed out of the process is expected to jump in on several fronts, including closer scrutiny of the published financial statements of public companies and financial institutions and the cottage industry of examining loan documents for compliance issues and violations of Federal and State lending laws.

20. Prospects for actual economic recovery affecting the average citizen are dim. While there has been considerable improvement from the point of risk we had reached at the end of 2008, the new President and Congress have yet to address essential reforms on joblessness, regulation of financial services (including insurance businesses permitted to write commitments without sufficient assets in reserve to assure the payment of the risk. The economic indicators have been undermined by the intentional fraud perpetrated upon the world economic and financial system. Thus the official figures are further than ever from revealing the truth about about our current status. Without key acceptance of these anomalies it is inconceivable that the economy will, in reality, improve during 2010.

21. Real inflation affecting everyday Americans has already started to rise as credit markets become increasingly remote from the prospective borrowers. Hyperinflation remains a risk although most of us were off on the timing because we underestimated the tenacious grip the dollar had on world commerce. While this assisted us in moving toward a softer landing, the probability that the dollar will continue to fall is still very high, thus making certain non-dollar denominated commodities more valuable. This phenomenon could affect housing prices in an upward direction if the trend continues. However the higher dollar prices will be offset by the fact that the cheaper dollars are required in greater quantities to buy anything. Thus the home prices might rise from $125,000 to $150,000 but the price of a loaf of bread will also be higher by 20%.

22. GDP has been skewed away from including econometrics for actual work performed in the home unless money changes hands. Societal values have thus depreciated the value of child-rearing and stable homes. The results have been catastrophic in education, crime, technological innovation and policy making. While GDP figures are officially announced as moving higher, the country continues to move further into a depression. No actual increase in GDP has occurred for many years, unless the declining areas of the society are excluded from what is counted.

23. The stock market is vastly overvalued again based upon vaporous forward earnings estimates and completely arbitrary price earnings ratios used by analysts. The vapor created by a 1000% increase in money supply caused by deregulation of the private financial institutions together with the illusion of profits created by these institutions trading between themselves has resulted in an increase from 16% to 45% of GDP activity. This figure is impossible to be real. As long as it is accepted as real or even possible, public figures, appointed and elected will base policy decisions on the desires of what is currently seen as the main driver of the U.S. economy. The balance of wealth will continue to move toward the levels of revolutionary France or the American colonies.

24. Perceptible increases in savings and consumer resistance to retail impulse buying bodes well for the long-term prospects of the country. As the savings class becomes more savvy and more wealthy, they will, like their counterparts in the upper echelons of government commence exercising their power in the marketplace and in the voting booth.

Edit : Edit

Comments : Leave a Comment »

Tags: 2923.5, eviction, Foreclosure, Fraud, litigation, Mortgage modification, Predatory Lending

Categories : 2923.5, 2923.6, 2924, Foreclosure, Predatory Lending, eviction, stop foreclosure

90% Forclosures Wrongful

1 01 2010

A wrongful foreclosure action typically occurs when the lender starts a non judicial foreclosure action when it simply has no legal cause. This is even more evident now since California passed the Foreclosure prevention act of 2008 SB 1194 codified in Civil code 2923.5 and 2923.6. In 2009 it is this attorneys opinion that 90% of all foreclosures are wrongful in that the lender does not comply (just look at the declaration page on the notice of default). The lenders most notably Indymac, Countrywide, and Wells Fargo have taken a calculated risk. To comply would cost hundreds of millions in staff, paperwork, and workouts that they don’t deem to be in their best interest. The workout is not in there best interest because our tax dollars are guaranteeing the Banks that are To Big to Fail’s debt. If they don’t foreclose and if they work it out the loss is on them. There is no incentive to modify loan for the benefit of the consumer.

Sooooo they proceed to foreclosure without the mandated contacts with the borrower. Oh and yes contact is made by a computer or some outsourcing contact agent based in India. But compliance with 2923.5 is not done. The Borrower is never told that he or she have the right to a meeting within 14 days of the contact. They do not get offers to avoid foreclosure there are typically two offers short sale or a probationary mod that will be declined upon the 90th day.

Wrongful foreclosure actions are also brought when the service providers accept partial payments after initiation of the wrongful foreclosure process, and then continue on with the foreclosure process. These predatory lending strategies, as well as other forms of misleading homeowners, are illegal.

The borrower is the one that files a wrongful disclosure action with the court against the service provider, the holder of the note and if it is a non-judicial foreclosure, against the trustee complaining that there was an illegal, fraudulent or willfully oppressive sale of property under a power of sale contained in a mortgage or deed or court judicial proceeding. The borrower can also allege emotional distress and ask for punitive damages in a wrongful foreclosure action.

Causes of Action

Wrongful foreclosure actions may allege that the amount stated in the notice of default as due and owing is incorrect because of the following reasons:

* Incorrect interest rate adjustment

* Incorrect tax impound accounts

* Misapplied payments

* Forbearance agreement which was not adhered to by the servicer

* Unnecessary forced place insurance,

* Improper accounting for a confirmed chapter 11 or chapter 13 bankruptcy plan.

* Breach of contract

* Intentional infliction of emotional distress

* Negligent infliction of emotional distress

* Unfair Business Practices

* Quiet title

* Wrongful foreclosure

* Tortuous violation of 2924 2923.5 and 2923.5 and 2932.5

Injunction

Any time prior to the foreclosure sale, a borrower can apply for an injunction with the intent of stopping the foreclosure sale until issues in the lawsuit are resolved. The wrongful foreclosure lawsuit can take anywhere from ten to twenty-four months. Generally, an injunction will only be issued by the court if the court determines that: (1) the borrower is entitled to the injunction; and (2) that if the injunction is not granted, the borrower will be subject to irreparable harm.

Damages Available to Borrower

Damages available to a borrower in a wrongful foreclosure action include: compensation for the detriment caused, which are measured by the value of the property, emotional distress and punitive damages if there is evidence that the servicer or trustee committed fraud, oppression or malice in its wrongful conduct. If the borrower’s allegations are true and correct and the borrower wins the lawsuit, the servicer will have to undue or cancel the foreclosure sale, and pay the borrower’s legal bills.

Why Do Wrongful Foreclosures Occur?

Wrongful foreclosure cases occur usually because of a miscommunication between the lender and the borrower. Most borrower don’t know who the real lender is. Servicing has changed on average three times. And with the advent of MERS Mortgage Electronic Registration Systems the “investor lender” hundreds of times since the origination. And now they then have to contact the borrower. The don’t even know who the lender truly is. The laws that are now in place never contemplated the virtualization of the lending market. The present laws are inadequate to the challenge.

This is even more evident now since California passed the Foreclosure prevention act of 2008 SB 1194 codified in Civil code 2923.5 and 2923.6. In 2009 it is this attorneys opinion that 90% of all foreclosures are wrongful in that the lender does not comply (just look at the declaration page on the notice of default). The lenders most notably Indymac, Countrywide, and Wells Fargo have taken a calculated risk. To comply would cost hundreds of millions in staff, paperwork, and workouts that they don’t deem to be in their best interest. The workout is not in there best interest because our tax dollars are guaranteeing the Banks that are To Big to Fail’s debt. If they don’t foreclose and if they work it out the loss is on them. There is no incentive to modify loan for the benefit of the consumer.This could be as a result of an incorrectly applied payment, an error in interest charges and completely inaccurate information communicated between the lender and borrower. Some borrowers make the situation worse by ignoring their monthly statements and not promptly responding in writing to the lender’s communications. Many borrowers just assume that the lender will correct any inaccuracies or errors. Any one of these actions can quickly turn into a foreclosure action. Once an action is instituted, then the borrower will have to prove that it is wrongful or unwarranted. This is done by the borrower filing a wrongful foreclosure action. Costs are expensive and the action can take time to litigate.

Impact

The wrongful foreclosure will appear on the borrower’s credit report as a foreclosure, thereby ruining the borrower’s credit rating. Inaccurate delinquencies may also accompany the foreclosure on the credit report. After the foreclosure is found to be wrongful, the borrower must then petition to get the delinquencies and foreclosure off the credit report. This can take a long time and is emotionally distressing.

Wrongful foreclosure may also lead to the borrower losing their home and other assets if the borrower does not act quickly. This can have a devastating affect on a family that has been displaced out of their home. However, once the borrower’s wrongful foreclosure action is successful in court, the borrower may be entitled to compensation for their attorney fees, court costs, pain, suffering and emotional distress caused by the action.

Edit : Edit

Comments : Leave a Comment »

Tags: 2923.5, 2923.5 2923.6 2924 2932.5 Audit bankruptcy california California cram down Chapter 13 civil code 2923.5 civil code 2924 Countrywide Cram down Cramdown criminal acts eviction FCRA FDCPA Federal Jurisdi, 2923.6, 2924, 2932.5, civil code 2924, Countrywide, Foreclosure, Fraud, stop foreclosure

Categories : 2923.5, 2923.6, 2924, Foreclosure, Lender Class action

TERRY MABRY et al., opinion 2923.5 Cilvil code

7 06 2010

CERTIFIED FOR PUBLICATION

IN THE COURT OF APPEAL OF THE STATE OF CALIFORNIA

FOURTH APPELLATE DISTRICT

DIVISION THREE

TERRY MABRY et al.,

Petitioners,

v.

THE SUPERIOR COURT OF ORANGE COUNTY,

Respondent;

AURORA LOAN SERVICES, et al.,

Real Parties in Interest.

G042911

(Super. Ct. No. 30-2009-003090696)

O P I N I O N

Original proceedings; petition for a writ of mandate to challenge an order of the Superior Court of Orange County, David C. Velazquez, Judge. Writ granted in part and denied in part.

Law Offices of Moses S. Hall and Moses S. Hall for Petitioners.

No appearance for Respondent.

Akerman Senterfitt, Justin D. Balser and Donald M. Scotten for Real Party in Interest Aurora Loan Services.

McCarthy & Holthus, Matthew Podmenik, Charles E. Bell and Melissa Robbins Contts for Real Party in Interest Quality Loan Service Corporation.

Bryan Cave, Douglas E. Winter, Christopher L. Dueringer, Sean D. Muntz and Kamae C. Shaw for Amici Curiae Bank of America and BAC Home Loans Servicing on behalf of Real Parties in Interest.

Wright, Finlay & Zak, Thomas Robert Finlay and Jennifer A. Johnson for Amici Curiae United Trustee’s Association and California Mortgage Association.

Leland Chan for Amicus Curiae California Bankers Association.

I. SUMMARY

Civil Code section 2923.5 requires, before a notice of default may be filed, that a lender contact the borrower in person or by phone to “assess” the borrower’s financial situation and “explore” options to prevent foreclosure. Here is the exact, operative language from the statute: “(2) A mortgagee, beneficiary, or authorized agent shall contact the borrower in person or by telephone in order to assess the borrower’s financial situation and explore options for the borrower to avoid foreclosure.” There is nothing in section 2923.5 that requires the lender to rewrite or modify the loan.

In this writ proceeding, we answer these questions about section 2923.5, also known as the Perata Mortgage Relief Act :

(A) May section 2923.5 be enforced by a private right of action? Yes. Otherwise the statute would be a dead letter.

(B) Must a borrower tender the full amount of the mortgage indebtedness due as a prerequisite to bringing an action under section 2923.5? No. To hold otherwise would defeat the purpose of the statute.

(C) Is section 2923.5 preempted by federal law? No — but, we must emphasize, it is not preempted because the remedy for noncompliance is a simple postponement of the foreclosure sale, nothing more.

(D) What is the extent of a private right of action under section 2923.5? To repeat: The right of action is limited to obtaining a postponement of an impending foreclosure to permit the lender to comply with section 2923.5.

(E) Must the declaration required of the lender by section 2923.5, subdivision (b) be under penalty of perjury? No. Such a requirement is not only not in the statute, but would be at odds with the way the statute is written.

(F) Does a declaration in a notice of default that tracks the language of section 2923.5, subdivision (b) comply with the statute, even though such language does not on its face delineate precisely which one of the three categories set forth in the declaration applies to the particular case at hand? Yes. There is no indication that the Legislature wanted to saddle lenders with the need to “custom draft” the statement required by the statute in notices of default.

(G) If a lender did not comply with section 2923.5 and a foreclosure sale has already been held, does that noncompliance affect the title to the foreclosed property obtained by the families or investors who may have bought the property at the foreclosure sale? No. The Legislature did nothing to affect the rule regarding foreclosure sales as final.

(H) In the present case, did the lender comply with section 2923.5? We cannot say on this record, and therefore must return the case to the trial court to determine which of the two sides is telling the truth. According to the lender, the borrowers themselves initiated a telephone conversation in which foreclosure-avoidance options were discussed, and there were many, many phone calls to the borrowers to attempt to discuss foreclosure-avoidance options. According to the borrowers, no one ever contacted them about nonforeclosure options. The trial judge, however, never reached this conflict in the facts, because he ruled strictly on legal grounds: namely (1) that section 2923.5 does not provide for a private right of action and (2) section 2923.5 is preempted by federal law. As indicated, we have concluded otherwise as to those two issues.

(I) Can section 2923.5 be enforced in a class action in this case? Not under these facts. The operation of section 2923.5 is highly fact-specific, and the details as to what might, or might not, constitute compliance can readily vary from lender to lender and borrower to borrower.

II. BACKGROUND

In December 2006, Terry and Michael Mabry refinanced the loan on their home in Corona from Paul Financial, borrowing about $700,000. In April 2008, Paul Financial assigned to Aurora Loan Services the right to service the loan. In this opinion, we will treat Aurora as synonymous with the lender and use the terms interchangeably.

According to the lender, in mid-July 2008 — before the Mabrys missed their August 2008 loan payment — the couple called Aurora on the telephone to discuss the loan with an Aurora employee. The discussion included mention of a number of options to avoid foreclosure, including loan modification, short sale, deed-in-lieu of foreclosure, and even a special forbearance. The Aurora employee sent a letter following up on the conversation. The letter explained the various options to avoid foreclosure, and asked the Mabrys to forward current financial information to Aurora so it could consider the Mabrys for these options.

According to the lender, the Mabrys missed their September 2008 payment as well, and mid-month Aurora sent them another letter describing ways to avoid foreclosure. Aurora employees called the Mabrys “many times” to discuss the situation. The Mabrys never picked up.

It is undisputed that later in September, the Mabrys filed Chapter 11 bankruptcy and Aurora did not contact the Mabrys while the bankruptcy was pending. (See 11 U.S.C. § 362 [automatic stay].) The Mabrys had their Chapter 11 case dismissed, however, in late March 2009.

According to the lender, Aurora once again began trying to call the Mabrys, calling them “numerous times,” including “three times on different days.” Meanwhile, in mid-April the Mabrys sent an authorization to discuss the loan with their lawyers.

According to the lender, finally, in June, the Mabrys sent two faxes to Aurora, the aggregate effect of which was to propose a short sale to the Mabrys’ attorney, Moses S. Hall, for $350,000. If accepted, the short sale would have meant a loss of over $400,000 on the loan. Aurora rejected that offer, and an attorney in Hall’s law office proposed a sale price of $425,000, which would have meant a loss to the lender of about $340,000.

It is undisputed that on June 18, 2009, Aurora recorded a notice of default. The notice of default used this (obviously form) language: “The Beneficiary or its designated agent declares that it has contacted the borrower, tried with due diligence to contact the borrower as required by California Civil Code section 2923.5, or the borrower has surrendered the property to the beneficiary or authorized agent, or is otherwise exempt from the requirements of section 2923.5.” Aurora sent six copies of the recorded notice of default to the Mabrys’ home by certified mail, and the certifications showed they were delivered.

It is also undisputed that on October 7, the Mabrys filed a complaint in Orange County Superior Court based on Aurora’s alleged failure to comply with section 2923.5.

According to the borrowers, no one had ever contacted them about their foreclosure options. Michael Mabry stated the following in his declaration: “We have never been contacted by Aurora nor [sic] any of its agents in person, by telephone or by first class mail to explore options for us to avoid foreclosure as required in CC § 2923.5.”

The complaint sought a temporary restraining order to prevent the foreclosure sale then scheduled just a week away, on October 14, 2009. Based on the allegation of no contact, the trial court issued a temporary restraining order, and scheduled a hearing for October 20.

But exactly one week before the October 20 hearing, the Mabrys filed an amended complaint, this one specifically adding class action allegations and seeking injunctive relief for an entire class. This new filing came with another request for a temporary restraining order, which was also granted, with a hearing on that temporary restraining order scheduled for October 27 (albeit the order was directed at Aurora only).

The first restraining order was vacated on October 20, the second on October 27. The trial judge did not, however, resolve the conflict in the facts presented by the pleadings. Rather he concluded: (1) the action is preempted by federal law; (2) there is no private right of action under section 2923.5 — the statute can only be enforced by members of pooling and servicing agreements; and (3) the Mabrys were required to at least tender all arrearages to enjoin any foreclosure proceedings.

The Mabrys filed a motion for reconsideration and a third request for a restraining order based on supposedly new law. The new law was a now review-granted Court of Appeal opinion which, let us merely note here, appears to have been quite off-point in regards to any issue which the trial judge had just decided. So it is not surprising that the requested restraining order was denied. The foreclosure sale was now scheduled for November 30, 2009. Six days before that, though, the Mabrys filed this writ proceeding, and two days later this court stayed all proceedings. We invited amicus curiae to give their views on the issues raised by the petition, and subsequently scheduled an order to show cause to consider those issues.

III. DISCUSSION

A. Private Right of Action? Yes

1. Preliminary Considerations

A private right of action may inhere within a statute, otherwise silent on the point, when such a private right of action is necessary to achieve the statute’s policy objectives. (E.g., Cannon v. University of Chicago (1979) 441 U.S. 677, 683 [implying private right of action into Title IX of the Civil Rights Act because such a right was necessary to achieve the statute’s policy objectives]; Basic Inc. v. Levinson (1988) 485 U.S. 224, 230-231 [implying private right of action to enforce securities statute].)

That is, the absence of an express private right of action is not necessarily preclusive of such a right. There are times when a private right of action may be implied by a statute. (E.g., Siegel v. American Savings & Loan Assn. (1989) 210 Cal.App.3d 953, 966 [“Before we reach the issue of exhaustion of administrative remedies, we must determine, therefore, whether plaintiffs have an implied private right of action under HOLA.”].)

California courts have, of recent date, looked to Moradi-Shalal v. Fireman’s Fund Ins. Companies (1988) 46 Cal.3d 287 (Moradi-Shalal) for guidance as to whether there is an implied private right of action in a given statute. In Moradi-Shalal, for example, the presence of a comprehensive administrative means of enforcement of a statute was one of the reasons the court determined that there was no private right of action to enforce a statute (Ins. Code, § 790.03, subd. (h)) regulating general insurance industry practices. (See Moradi-Shalal, supra, 46 Cal.3d at p. 300.)

There is also a pre-Moradi Shalal approach, embodied in Middlesex Ins. Co. v. Mann (1981) 124 Cal.App.3d 558, 570 (Middlesex). (The Middlesex opinion itself copied the idea from the Restatement Second of Torts, section 874A.) The approach looks to whether a private remedy is “appropriate” to further the “purpose of the legislation” and is “needed to assure the effectiveness of the provision.” (Middlesex, supra, 124 Cal.App.3d at p. 570.)

Obviously, where the two approaches conflict, the one used by our high court in Moradi-Shalal trumps the Middlesex approach. But we may note at this point that as regards section 2923.5, there is no alternative administrative mechanism to enforce the statute. By contrast, in Moradi-Shalal, there was an existing administrative mechanism at hand (by way of the Insurance Commissioner) available to enforce section 790.03, subdivision (h) of the Insurance Code.

There are other corollary principles as well.

First, California courts, quite naturally, do not favor constructions of statutes that render them advisory only, or a dead letter. (E.g., Petropoulos v. Department of Real Estate (2006) 142 Cal.App.4th 554, 567; People v. Stringham (1988) 206 Cal.App.3d 184, 197.) Our colleagues in Division One of this District nicely summarized this point in Goehring v. Chapman University (2004) 121 Cal.App.4th 353, 375: “The question of whether a regulatory statute creates a private right of action depends on legislative intent . . . . In determining legislative intent, ‘[w]e first examine the words themselves because the statutory language is generally the most reliable indicator of legislative intent . . . . The words of the statute should be given their ordinary and usual meaning and should be construed in their statutory context. . . . These canons generally preclude judicial construction that renders part of the statute “meaningless or inoperative.”‘” (Italics added.)

Second, statutes on the same subject matter or of the same subject should be construed together so that all the parts of the statutory scheme are given effect. (Lexin v. Superior Court (2010) 47 Cal.4th 1050, 1090-1091.) This canon is particularly important in the case before us, where there is an enforcement mechanism available at hand to enforce section 2923.5, in the form, as we explain below, of section 2924g. Ironically though, the enforcement mechanism at hand, in direct contrast to the one in Moradi-Shalal, is one that strongly implies individual enforcement of the statute.

Third, historical context can also shed light on whether the Legislature intended a private right of action in a statute. As noted by one federal district court that has found a private right of action in section 2923.5, the fact that a statute was enacted as an emergency statute is an important factor in determining legislative intent. (See Ortiz v. Accredited Home Lenders, Inc. (S.D. 2009) 639 F.Supp.2d 1159, 1166 [agreeing with argument that “the California legislature would not have enacted this ‘urgency’ legislation, intended to curb high foreclosure rates in the state, without any accompanying enforcement mechanism”]; cf. County of San Diego v. State of California (2008) 164 Cal.App.4th 580, 609 [admitting that private right of action might exist, even if the Legislature did not imply one, if “‘compelling reasons of public policy'” required “judicial recognition of such a right”].) Section 2923.5 was enacted in 2008 as a manifestation of a felt need for urgent action in the midst of a cascading torrent of foreclosures.

Finally, of course, there is recourse to legislative history. Alas, in this case, there is silence on the matter as regards the existence of a private right of action in the final draft of the statute, and we have been cited to nothing in the history that suggests a clear legislative intent one way or the other. (See generally J.A. Jones Construction Co. v. Superior Court (1994) 27 Cal.App.4th 1568, 1575 (J.A. Jones) [emphasizing importance of clear intent appearing in legislative history].) To be sure, as we were reminded at oral argument, an early version of section 2923.5 had an express provision for a private right of action and that provision did not make its way into the final version of the statute. And we recognize that this factor suggests the Legislature may not have wanted to have section 2923.5 enforced privately.

On the other hand, the bottom line was an outcome of silence, not a clear statement that there should be no individual enforcement. And silence, as this court pointed out in J.A. Jones, has its own implications. There, we cited Professor Eskridge’s work on statutory interpretation (see Eskridge, The New Textualism (1990) 37 U.C.L.A. L.Rev. 621, 670-671 (hereinafter “Eskridge on Textualism”)) to recognize that ambiguity in a statute may itself be the result of both sides in the legislative process agreeing to let the courts decide a point: “[I]f there is ambiguity it is because the legislature either could not agree on clearer language or because it made the deliberate choice to be ambiguous — in effect, the only ‘intent’ is to pass the matter on to the courts.” (J.A. Jones, supra, 27 Cal. App.4th at p. 1577.) As Professor Eskridge put it elsewhere in his article: “The vast majority of the Court’s difficult statutory interpretation cases involve statutes whose ambiguity is either the result of deliberate legislative choice to leave conflictual decisions to agencies or the courts.” (Eskridge on Textualism, supra, 37 UCLA L.Rev. at p. 677.)

We have a concrete example in the case at hand. Amicus curiae, the California Bankers Association, asserts that if section 2923.5 had included an express right to a private right of action, the association would have vociferously opposed the legislation. Let us accept that as true. But let us also accept as a reasonable premise that the sponsors of the bill (2008, Senate Bill No. 1137) would have vociferously opposed the legislation if it had an express prohibition on individual enforcement. The point is, the bankers did not insist on language expressly or even impliedly precluding a private right of action, or, if they did, they didn’t get it. The silence is consonant with the idea that section 2923.5 was the result of a legislative compromise, with each side content to let the courts struggle with the issue.

With these observations, we now turn to the language, structure and function of the statute at issue.

2. Operation of Section 2923.5

Section 2923.5 is one of a series of detailed statutes that govern mortgages that span sections 2920 to 2967. Within that series is yet another long series of statutes governing rules involving foreclosure. This second series goes from section 2924, and then follows with sections 2924a through 2924l. (There is no section 2924m . . . yet.)

Section 2923.5 concerns the crucial first step in the foreclosure process: The recording of a notice of default as required by section 2924. (Just plain section 2924 — this one has no lower case letter behind it.)

The key text of section 2923.5 — “key” because of the substantive obligation it imposes on lenders — basically says that a lender cannot file a notice of default until the lender has contacted the borrower “in person or by telephone.” Thus an initial form letter won’t do. To quote the text directly, lenders must contact the borrower by phone or in person to “assess the borrower’s financial situation and explore options for the borrower to avoid foreclosure.” The statute, of course, has alternative provisions in cases where the lender tries to contact a borrower, and the borrower simply won’t pick up the phone, the phone has been disconnected, the borrower hides or otherwise evades contact.

The contrast between section 2923.5 and one of its sister-statutes, section 2923.6, is also significant. By its terms, section 2923.5 operates substantively on lenders. They must do things in order to comply with the law. In Hohfeldian language, it both creates rights and corresponding obligations.

But consider section 2923.6, which does not operate substantively. Section 2923.6 merely expresses the hope that lenders will offer loan modifications on certain terms. By contrast, section 2923.5 requires a specified course of action. (There is a reason for the difference, as we show in part III.C., dealing with federal preemption. In a word, to have required loan modifications would have run afoul of federal law.)

As noted above, other steps in the foreclosure process are set forth in sections 2924a through 2924l. The topic of the postponement of foreclosure sales is addressed in section 2924g.

Subdivision (c)(1)(A) of section 2924g sets forth the grounds for postponements of foreclosure sales. One of those grounds is the open-ended possibility that any court of competent jurisdiction may issue an order postponing the sale. Section 2923.5 and section 2924g, subdivision (c)(1)(A), when read together, establish a natural, logical whole, and one wholly consonant with the Legislature’s intent in enacting 2923.5 to have individual borrowers and lenders “assess” and “explore” alternatives to foreclosure: If section 2923.5 is not complied with, then there is no valid notice of default, and without a valid notice of default, a foreclosure sale cannot proceed. The available, existing remedy is found in the ability of a court in section 2924g, subdivision (c)(1)(A), to postpone the sale until there has been compliance with section 2923.5. Reading section 2923.5 together with section 2924g, subdivision (c)(1)(A) gives section 2923.5 real effect. The alternative would mean that the Legislature conferred a right on individual borrowers in section 2923.5 without any means of enforcing that right.

By the same token, compliance with section 2923.5 is necessarily an individualized process. After all, the details of a borrower’s financial situation and the options open to a particular borrower to avoid foreclosure are going to vary, sometimes widely, from borrower to borrower. Section 2923.5 is not a statute, like subdivision (h) of section 790.03 of the Insurance Code construed in Moradi-Shalal, which contemplates a frequent or general business practice, and thus its very text is necessarily directed at those who regulate the insurance industry. (Insurance Code section 790.03, subdivision (h) begins with the words, “Knowingly committing or performing with such frequency as to indicate a general business practice any of the following unfair claims settlement practices: . . . .”; see generally Moradi-Shalal, supra, 46 Cal.3d 287.)

Rather, in order to have its obvious goal of forcing parties to communicate (the statutory words are “assess” and “explore”) about a borrower’s situation and the options to avoid foreclosure, section 2923.5 necessarily confers an individual right. The alternative proffered by the trial court — enforcement by the servicer of pooling agreements — involves the facially unworkable problem of fitting individual situations into collective pools.

The suggestion of one amicus that the Legislature intended enforcement of section 2923.5 to reside within the Attorney General’s office is one of which we express no opinion. Our decision today should thus not be read as precluding such enforcement by the Attorney General’s office. But we do note that the same individual-collective problem would dog Attorney General enforcement of the statute. To be sure (which is why the possibility should be left open), there might, ala Insurance Code section 790.03, subdivision (h), be lenders who systematically ignore section 2923.5, and their “general business practice” would be susceptible to some sort of collective enforcement. Even so, the Attorney General’s office can hardly be expected to take up the cause of every individual borrower whose diverse circumstances show noncompliance with section 2923.5.

3. Application

We now put the preceding ideas and factors together.

While the dropping of an express provision for private enforcement in the legislative process leading to section 2923.5 does indeed give us pause, it is outweighed by two major opposing factors. First, the very structure of section 2923.5 is inherently individual. That fact strongly suggests a legislative intention to allow individual enforcement of the statute. The statute would become a meaningless dead letter if no individual enforcement were allowed: It would mean that the Legislature created an inherently individual right and decided there was no remedy at all.

Second, when section 2923.5 was enacted as an urgency measure, there already was an existing enforcement mechanism at hand — section 2924g. There was no need to write a provision into section 2923.5 allowing a borrower to obtain a postponement of a foreclosure sale, since such a remedy was already present in section 2924g. Reading the two statutes together as allowing a remedy of postponement of foreclosure produces a logical and natural whole.

B. Tender Full Amount of Indebtedness? No

The right conferred by section 2923.5 is a right to be contacted to “assess” and “explore” alternatives to foreclosure prior to a notice of default. It is enforced by the postponement of a foreclosure sale. Therefore it would defeat the purpose of the statute to require the borrower to tender the full amount of the indebtedness prior to any enforcement of the right to — and that’s the point — the right to be contacted prior to the notice of default. Case law requiring payment or tender of the full amount of payment before any foreclosure sale can be postponed (e.g., Arnolds Management Corp. v. Eischen (1984) 158 Cal.App.3d 575, 578 [“It is settled that an action to set aside a trustee’s sale for irregularities in sale notice or procedure should be accompanied by an offer to pay the full amount of the debt for which the property was security.”]) arises out of a paradigm where, by definition, there is no way that a foreclosure sale can be avoided absent payment of all the indebtedness. Any irregularities in the sale would necessarily be harmless to the borrower if there was no full tender. (See 4 Miller & Starr, Cal. Real Estate (2d ed. 1989) § 9:154, pp. 507-508.) By contrast, the whole point of section 2923.5 is to create a new, even if limited right, to be contacted about the possibility of alternatives to full payment of arrearages. It would be contradictory to thwart the very operation of the statute if enforcement were predicated on full tender. It is well settled that statutes can modify common law rules. (E.g., Evangelatos v. Superior Court

44 Cal.3d 1188, 1192 [noting that Civil Code sections 1431 to 1431.5 had modified traditional common law doctrine of joint and several liability].)

C. Preempted by Federal Law? No — As Long

As Relief Under Section 2923.5 is Limited to Just Postponement

1. Historical Context

A remarkable aspect of section 2923.5 is that it appears to have been carefully drafted to avoid bumping into federal law, precisely because it is limited to affording borrowers only more time when lenders do not comply with the statute. To explain that, though, we need to make a digression into state debtors’ relief acts as they have manifested themselves in four previous periods of economic distress.

The first period of economic distress was the depression of the mid-1780’s that played a large part in engendering the United States Constitution in the first place. As Chief Justice Charles Evans Hughes would later note for a majority of the United States Supreme Court, there was “widespread distress following the revolutionary period and the plight of debtors, had called forth in the States an ignoble array of legislative schemes for the defeat of creditors and the invasion of contractual obligations.” (Home Building and Loan Ass’n. v. Blaisdell (1934) 290 U.S. 398, 427 (Blaisdell).) Consequently, the federal Constitution of 1789 contains the contracts clause, which forbids states from impairing contracts. (See Siegel, Understanding the Nineteenth Century Contract Clause: The Role of the Property-Privilege Distinction and ‘Takings’ Clause Jurisprudence (1986) 60 So.Cal. L.Rev. 1, 21, fn. 86 [“Although debtor relief legislation was frequently enacted in the Confederation era, it was intensely opposed. It was among the chief motivations for the convening of the Philadelphia convention, and the Constitution drafted there was designed to eliminate such legislation through a variety of means.”].)

The second period of distress arose out of the panic of 1837, which prompted, in 1841, the Illinois state legislature to enact legislation severely restricting foreclosures. The legislation (1) gave debtors 12 months after any foreclosure sale to redeem the property; and (2) prevented any foreclosure sale in the first place unless the sale fetched at least two-thirds of the appraised value of the property. (See Bronson v. Kinzie (1843) 42 U.S. 311 (Bronson); Blaisdell, supra, 290 U.S. at p. 431.) In an opinion, the main theme of which is the interrelationship between contract rights and legal remedies to enforce those rights (see generally Bronson, supra, 42 U.S. at pp. 315-321), the Bronson court reasoned that the Illinois legislation had effectively destroyed the contract rights of the lender as regards a mortgage made in 1838. (See id. at p. 317 [“the obligation of the contract, and the rights of a party under it, may, in effect, be destroyed by denying a remedy altogether”].)

The third period of distress was, of course, the Great Depression of the 1930’s. In 1933, the Minnesota Legislature enacted a mortgage moratorium law that extended the period of redemption under Minnesota law until 1935. (See Blaisdell, supra, 290 U.S. at pp. 415-416.) But — and the high court majority found this significant — the law required debtors, in applying for an extension of the redemption period — to pay the reasonable value of the income of the property, or reasonable rental value if it didn’t produce income. (Id. at. pp. 416-417.) The legislation was famously upheld in Blaisdell. In distinguishing Bronson, the Blaisdell majority made the point that the statute did not substantively impair the debt the way the legislation in Bronson had: “The statute,” said the court, “does not impair the integrity of the mortgage indebtedness.” (Id. at p. 425.) The court went on to emphasize the need to pay the fair rental value of the property, which, it noted, was “the equivalent of possession during the extended period.”

Finally, the fourth period was within the living memory of many readers, namely, the extraordinary inflation and high interest rates of the late 1970’s. That period engendered Fidelity Federal Savings & Loan Association v. de la Cuesta (1982) 458 U.S. 141 (de la Cuesta). Many mortgages had (still have) what is known as a “due-on-sale” clause. As it played out in the 1970’s, the clause effectively required any buyer of a new home to obtain a new loan, but at the then-very high market interest rates. To circumvent the need for a new high rate mortgage, creative wrap-around financing was invented where a buyer would assume the obligation of the old mortgage, but that required the due-on-sale clause not be enforced.

An earlier decision of the California Supreme Court, Wellenkamp v. Bank of America (1978) 21 Cal.3d 943, had encouraged this sort of creative financing by holding that due-on-sale clauses violated California state law as an unreasonable restraint on alienation. Despite that precedent, the trial judge in the de la Cuesta case (Edward J. Wallin, who would later join this court) held that regulations issued by the Federal Home Loan Bank Board, by the authority of the Home Owners’ Loan Act of 1933 preempted state law that invalidated due-on-sale clause. A California appellate court in the Fourth District (in an opinion by Justice Marcus Kaufman, who would later join the California Supreme Court) reversed the trial court. The United States Supreme Court, however, agreed with Judge Wallin’s determination, and reversed the appellate judgment and squarely held the state law to be preempted.

The de la Cuesta court observed that the bank board’s regulations were plain — “even” the California appellate court had been required to recognize that. (de la Cuesta, supra, 458 U.S. at p. 154). On top of the express preemption, Congress had expressed no intent to limit the bank board’s authority to “regulate the lending practices of federal savings and loans.” (Id. at p. 161.) Further, going into the history of the Home Owners’ Loan Act, the de la Cuesta court pointed out that “mortgage lending practices” are a “critical” aspect of a savings and loan’s “‘operation,'” and the Home Loan Bank Board had issued the due-on-sale regulations in order to protect the economic solvency of such lenders. (See id. at pp. 167-168.) In what is perhaps the most significant part of the rationale for our purposes, the bank board had concluded that “the due-on-sale clause is ‘an important part of the mortgage contract,'” consequently its elimination would have an adverse effect on the “financial stability” of federally chartered lenders. (Id. at p. 168.) For example, invalidation of the due-on-sale clause would make it hard for savings and loans “to sell their loans in the secondary markets.” (Ibid.)

With this history behind us, we now turn to the actual regulations at issue in the case before us.

2. The HOLA Regulations

Under the Home Owner’s Loan Act of 1933 (12 U.S.C. § 1461 et seq.) the federal Office of Thrift Supervision has issued section 560.2 of title 12 of the Code of Federal Regulations, a regulation that itself delineates what is a matter for federal regulation, and what is a matter for state law. Interestingly enough, section 560.2 is written in the form of examples, using the “ejusdem generis” approach of requiring a court to figure out what is, and what is not, in the same general class or category as the items given in the example.

On the preempted side, section 560.2 includes:

– “terms of credit, including amortization of loans and the deferral and capitalization of interest and adjustments to the interest rate” (§ 560.2(b)(4));

– “balance, payments due, or term to maturity of the loan” (§ 560.2(b)(4)); and, most importantly for this case,

– the “processing, origination, servicing, sale or purchase of, or investment or participation in, mortgages.” (§ 560.2(b)(10), italics added.)

On the other side, left for the state courts, is “Real property law.” (12 C.F.R. § 560.2(c)(2).)

We agree with the Mabrys that the process of foreclosure has traditionally been a matter of state real property law, a point both noted by the United States Supreme Court in BFP v. Resolution Trust Corp. (1994) 511 U.S. 531, 541-542, and academic commentators (e.g., Alexander, Federal Intervention in Real Estate Finance: Preemption and Federal Common Law (1993) 71 N.C. L. Rev. 293, 293 [“Historically, real property law has been the exclusive domain of the states.”]), including at least one law professor who laments that diverse state foreclosure laws tend to hinder efforts to achieve banking stability at the national level. (See Nelson, Confronting the Mortgage Meltdown: A Brief for the Federalization of State Mortgage Foreclosure Law (2010) 37 Pepperdine L.Rev. 583, 588-590 [noting that mortgage foreclosure law varies from state to state, and advocating federalization of mortgage foreclosure law].) By contrast, we have not been cited to anything in the federal regulations that govern such things as initiation of foreclosure, notice of foreclosure sales, allowable times until foreclosure, or redemption periods. (Though there are commentators, like Professor Nelson, who argue there should be.)

Given the traditional state control over mortgage foreclosure laws, it is logical to conclude that if the Office of Thrift Supervision wanted to include foreclosure as within the preempted category of loan servicing, it would have been explicit. Nothing prevented the office from simply adding the words “foreclosure of” to section 560.2(b)(10).

D. The Extent of Section 2923.5?

More Time and Only More Time

State law should be construed, whenever possible, to be in harmony with federal law, so as to avoid having the state law invalidated by federal preemption. (See Greater Westchester Homeowners Assn. v. City of Los Angeles (1979) 26 Cal.3d 86, 93; California Arco Distributors, Inc. v. Atlantic Richfield Co. (1984) 158 Cal.App.3d 349, 359.)

We emphasize that we are able to come to our conclusion that section 2923.5 is not preempted by federal banking regulations because it is, or can be construed to be, very narrow. As mentioned above, there is no right, for example, under the statute, to a loan modification.

A few more comments on the scope of the statute:

First, to the degree that the words “assess” and “explore” can be narrowly or expansively construed, they must be narrowly construed in order to avoid crossing the line from state foreclosure law into federally preempted loan servicing. Hence, any “assessment” must necessarily be simple — something on the order of, “why can’t you make your payments?” The statute cannot require the lender to consider a whole new loan application or take detailed loan application information over the phone. (Or, as is unlikely, in person.)

Second, the same goes for any “exploration” of options to avoid foreclosure. Exploration must necessarily be limited to merely telling the borrower the traditional ways that foreclosure can be avoided (e.g., deeds “in lieu,” workouts, or short sales), as distinct from requiring the lender to engage in a process that would be functionally indistinguishable from taking a loan application in the first place. In this regard, we note that section 2923.5 directs lenders to refer the borrower to “the toll-free telephone number made available by the United States Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) to find a HUD-certified housing counseling agency.” The obvious implication of the statute’s referral clause is that the lender itself does not have any duty to become a loan counselor itself.

Finally, to the degree that the “assessment” or “exploration” requirements impose, in practice, burdens on federal savings banks that might arguably push the statute out of the permissible category of state foreclosure law and into the federally preempted category of loan servicing or loan making, evidence of such a burden is necessary before the argument can be persuasive. For the time being, and certainly on this record, we cannot say that section 2923.5, narrowly construed, strays over the line.

Given such a narrow construction, section 2923.5 does not, as the law in Blaisdell did not, affect the “integrity” of the basic debt. (Cf. Lopez v. World Savings & Loan Assn. (2003) 105 Cal.App.4th 729 [section 560.2 preempted state law that capped payoff demand statement fees].)

E. The Wording of the Declaration:

Okay If Not Under Penalty of Perjury

In addition to the substantive act of contacting the borrower, section 2923.5 requires a statement in the notice of default. The statement is found in subdivision (b), which we quote here: “(b) A notice of default filed pursuant to Section 2924 shall include a declaration that the mortgagee, beneficiary, or authorized agent has contacted the borrower, has tried with due diligence to contact the borrower as required by this section, or that no contact was required pursuant to subdivision (h).” (Italics added.)

The idea that this “declaration” must be made under oath must be rejected. First, ordinary English usage of the word “declaration” imports no requirement that it be under oath. In the Oxford English Dictionary, for example, numerous definitions of the word are found, none of which of require a statement under oath or penalty of perjury. In fact, the second legal definition given actually juxtaposes the idea of a declaration against the idea of a statement under oath: “A simple affirmation to be taken, in certain cases, instead of an oath or solemn affirmation.” (4 Oxford English Dict. (2d. ed. 1991) at p. 336.)

Second, even the venerable Black’s Law Dictionary doesn’t define “declaration” to necessarily be under oath. Its very first definition of the word is: “A formal statement, proclamation or announcement, esp. one embodied in an instrument.” (Black’s Law Dict. (9th ed. 2009) at p. 467.)

Third, if the Legislature wanted to say that the statement required in section 2923.5 must be under penalty of perjury, it knew how to do so. The words “penalty of perjury” are used in other laws governing mortgages. (E.g., § 2941.7, subdivision (b) [“The declaration provided for in this section shall be signed by the mortgagor or trustor under penalty of perjury.”].)

And, finally — back to our point about the inherent individual operation of the statute — the very structure of subdivision (b) belies any insertion of a penalty of perjury requirement. The way section 2923.5 is set up, too many people are necessarily involved in the process for any one person to likely be in the position where he or she could swear that all three requirements of the declaration required by subdivision (b) were met. We note, for example, that subdivision (a)(2) requires any one of three entities (a “mortgagee, beneficiary, or authorized agent”) to contact the borrower, and such entities may employ different people for that purpose. And the option under the statute of no contact being required (per subdivision (h) ) further involves individuals who would, in any commercial operation, probably be different from the people employed to do the contacting. For example, the person who would know that the borrower had surrendered the keys would in all likelihood be a different person than the legal officer who would know that the borrower had filed for bankruptcy.

The argument for requiring the declaration to be under penalty of perjury relies on section 2015.5 of the Code of Civil Procedure, but that reliance is misplaced. We quote all of section 2015.5 in the margin. Essentially the statute says if a statement in writing is required to be supported by sworn oath, making the statement under penalty of perjury will be sufficient. The key language is: “Whenever, under any law of this state . . . made pursuant to the law of this state, any matter is required . . . to be . . . evidenced . . . by the sworn . . . declaration . . . in writing of the person making the same . . . such matter may with like force and effect be . . . evidenced . . . by the unsworn . . . declaration . . . in writing of such person which recites that it is . . . declared by him or her to be true under penalty of perjury . . . .” (Italics added.) The section sheds no light on whether the declaration required in section 2923.5, subdivision (b) must be under penalty of perjury.

F. The Wording of the Declaration:

Okay If It Tracks the Statute

In light of what we have just said about the multiplicity of persons who would necessarily have to sign off on the precise category in subdivision (b) of the statute that would apply in order to proceed with foreclosure (contact by phone, contact in person, unsuccessful attempts at contact by phone or in person, bankruptcy, borrower hiring a foreclosure consultant, surrender of keys), and the possibility that such persons might be employees of not less than three entities (mortgagee, beneficiary, or authorized agent), there is no way we can divine an intention on the part of the Legislature that each notice of foreclosure be custom drafted.

To which we add this important point: By construing the notice requirement of section 2923.5, subdivision (b), to require only that the notice track the language of the statute itself, we avoid the problem of the imposition of costs beyond the minimum costs now required by our reading of the statute.

G. Noncompliance Before Foreclosure

Sale Affect Title After Foreclosure Sale? No

A primary reason for California’s comprehensive regulation of foreclosure in the Civil Code is to ensure stability of title after a trustee’s sale. (Melendrez v. D & I Investment, Inc. (2005) 127 Cal.App.4th 1238, 1249-1250 [“comprehensive statutory scheme” governing foreclosure has three purposes, one of which is “to ensure that a properly conducted sale is final between the parties and conclusive as to a bona fide purchaser” (internal quotations omitted)].)

There is nothing in section 2923.5 that even hints that noncompliance with the statute would cause any cloud on title after an otherwise properly conducted foreclosure sale. We would merely note that under the plain language of section 2923.5, read in conjunction with section 2924g, the only remedy provided is a postponement of the sale before it happens.

H. Lender Compliance in This Case?

Somebody is Not Telling the Truth

and It’s the Trial Court’s Job to

Determine Who It Is

We have already recounted the conflict in the evidence before the trial court regarding whether there was compliance with section 2923.5. Rarely, in fact, are stories so diametrically opposite: According to the Mabrys, there was no contact at all. According to Aurora, not only were there numerous contacts, but the Mabrys even initiated a proposal by which their attorney would buy the property.

Somebody’s not telling the truth, but appellate courts do not resolve conflicts in evidence. Trial courts do. (Butt v. State of California (1992) 4 Cal.4th 668, 697, fn. 23 [“Moreover, Diaz and Bezemek concede the proffered evidence is disputed; appellate courts will not resolve such factual conflicts.”].) This case will obviously have to be remanded for an evidentiary hearing.

I. Is This Case Suitable for

Class Action Treatment? No

As we have seen, section 2923.5 contemplates highly-individuated facts. One borrower might not pick up the telephone, one lender might only call at the same time each day in violation of the statute, one lender might (incorrectly) try to get away with a form letter, one borrower might, like the old Twilight Zone “pitchman” episode, try to keep the caller on the line but change the subject and talk about anything but alternatives to foreclosure, one borrower might, as Aurora asserts here, try to have his or her attorney do a deal that avoids foreclosure, etcetera.

In short, how in the world would a court certify a class? Consider that in this case, there is even a dispute over the basic facts as to whether the lender attempted to comply at all. We do not have, under these facts at least, a question of a clean, systematic policy on the part of a lender that might be amenable to a class action (or perhaps enforcement by the Attorney General). This case is not one, to be blunt, where the lender admits that it simply ignored the statute and proceeded on the theory that federal law had preempted it. We express no opinion as to any scenario where a lender simply ignored the statute wholesale — that sort of scenario is why we do not preclude, a priori, class actions and have not expressed an opinion as to whether the Attorney General or a private party in such a situation might indeed seek to enforce section 2923.5 in a class action.

Consequently, while we must grant the writ petition so as to allow the Mabrys a hearing on the factual merits of compliance, we deny it insofar as it seeks reinstatement of any claims qua class action. By the same token, in light of the limited right to time conferred under section 2923.5, we also deny the writ petition insofar as it seeks reinstatement of any claim for money damages.

IV. CONCLUSION

Let a writ issue instructing the trial court to decide whether or not Aurora complied with section 2923.5. To the degree that the trial court’s order precludes the assertion of any class action claims, we deny the writ. If the trial court finds that Aurora has complied with section 2923.5, foreclosure may proceed. If not, it shall be postponed until Aurora files a new notice of default in the wake of substantive compliance with section 2923.5.

Given that this writ petition is granted in part and denied in part, each side will bear its own costs in this proceeding.

SILLS, P. J.

WE CONCUR:

ARONSON, J.

IKOLA, J.

Edit : Edit

Comments : Leave a Comment »

Tags: stop foreclosure, Mortgage modification, mortgage meltdown, Foreclosure, 2923.5

Categories : 2923.5, 2923.6, Foreclosure

Latest on MERS and “possession of the Note”

3 04 2010

There is a great case re MERS’ authority to operate in CA since it is NOT registered to do business. The case is Champlaie. It

states that MERS is not a foreign lending institution, nor is it creating evidences.

The case is also interesting since it discusses why those who foreclose do not have to be in possession of the promissory note.Here are three paragraphs below from the court, although they are taken from different pages.

It is not helpful for us but the court does question why those who foreclose do not have to be in possession of the note.

“Several courts have held that this language demonstrates that possession of the note is not required, apparently concluding that the statute authorizes initiation of foreclosure by parties who would not be expected to possess the

note. See, e.g., Spencer v. DHI Mortg. Co., No. 09-0925, 2009 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 55191, *23-*24, 2009 WL 1930161 (E.D. Cal. June 30, 2009) (O’Neill, J.).

However, the precise reasoning of these cases is unclear.FN14″

“To say that a trustee’s duties are strictly limited does not appear to this court to preclude possession of the note as a prerequisite to foreclosure. On the other hand, perhaps it is not unreasonable to suggest that such a prerequisite imposes a nonstatutory duty.”

“At some point, however, the opinion of a large number of decisions, while not in a sense binding, are by virtue of the sheer number, determinative. I cannot conclude that the result reached by the district courts is unreasonable or does not accord with the law. I further note that this conclusion is not obviously at odds with the policies underlying the California statutes. The apparent purpose

of requiring possession of a negotiable instrument is to avoid fraud. In the context of non-judicial foreclosures, however, the danger of fraud is minimized by the requirement that the deed of trust be recorded, as must be any assignment or substitution of the parties thereto. While it may be that requiring production of the note would have done something to limit the mischief that led to the economic pain the nation has suffered, the great weight of authority has reasonably concluded that California law does not impose this requirement.”

Edit : Edit

Comments : 1 Comment »

Tags: 2923.5, 2923.5 2923.6 2924 2932.5 Audit bankruptcy california California cram down Chapter 13 civil code 2923.5 civil code 2924 Countrywide Cram down Cramdown criminal acts eviction FCRA FDCPA Federal Jurisdi, Foreclosure, Fraud

Categories : 2923.5, Foreclosure, I Have a Plan, mortgage meltdown, pedatory lending, stop foreclosure

Latest ruling on Civil Code 2923.5

26 02 2010

B. Perata Mortgage Relief Act, Cal. Civ. Code § 2923.5

Plaintiffs’ second cause of action arises under the Perata Mortgage Relief Act, Cal. Civ. Code § 2923.5. Plaintiffs argue U.S. Bank is liable for monetary damages under this provision because it “failed and refused to explore” “alternatives to the drastic remedy of foreclosure, such as loan modifications” before initiating foreclosure proceedings. (FAC PP 17-18.) Furthermore, Plaintiffs allege U.S. Bank violated Cal. Civ. Code § 2923.5(c) by failing to include with the notice of sale a declaration that it contacted the borrower to explore such options. (Opp’n at 6.)

Section 2923.5(a)(2) requires a “mortgagee, beneficiary or authorized agent” to “contact the borrower in person or by telephone in order to assess the borrower’s [*1166] financial situation and explore options for the borrower to avoid foreclosure.” For a lender which had recorded a notice of default prior to the effective date of the statute, as is the case here, § 2923.5(c) imposes a duty to attempt to negotiate with a borrower before recording a notice of sale. These provisions cover loans initiated between January 1, 2003 and December 31, 2007. Cal. Civ. Code § 2923.5(h)(3), (i).

U.S. Bank’s primary argument is that Plaintiffs’ claim should be dismissed because neither § 2923.5 nor its legislative history clearly indicate an intent to create a private right of action. (Mot. at 8.) Plaintiffs counter that such a conclusion is unsupported by the legislative history; the California legislature would not have enacted this “urgency” legislation, intended to curb high foreclosure rates in the state, without any accompanying enforcement mechanism. (Opp’n at 5.) The court agrees with Plaintiffs. While the Ninth Circuit has yet to address this issue, the court found no decision from this circuit [**15] where a § 2923.5 claim had been dismissed on the basis advanced by U.S. Bank. See, e.g. Gentsch v. Ownit Mortgage Solutions Inc., 2009 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 45163, 2009 WL 1390843, at *6 (E.D. Cal., May 14, 2009)(addressing merits of claim); Lee v. First Franklin Fin. Corp., 2009 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 44461, 2009 WL 1371740, at *1 (E.D. Cal., May 15, 2009) (addressing evidentiary support for claim).

On the other hand, the statute does not require a lender to actually modify a defaulting borrower’s loan but rather requires only contacts or attempted contacts in a good faith effort to prevent foreclosure. Cal. Civ. Code § 2923.5(a)(2). Plaintiffs allege only that U.S. Bank “failed and refused to explore such alternatives” but do not allege whether they were contacted or not. (FAC P 18.) Plaintiffs’ use of the phrase “refused to explore,” combined with the “Declaration of Compliance” accompanying the Notice of Trustee’s Sale, imply Plaintiffs were contacted as required by the statute. (Doc. No. 7-2, Exh. 4 at 3.) Because Plaintiffs have failed to state a claim under Cal. Civ. Code § 2923.5, U.S. Bank’s motion to dismiss is granted. Plaintiffs’ claim is dismissed without prejudice.

Edit : Edit

Comments : 8 Comments »

Tags: 2923.5, 2923.5 2923.6 2924 2932.5 Audit bankruptcy california California cram down Chapter 13 civil code 2923.5 civil code 2924 Countrywide Cram down Cramdown criminal acts eviction FCRA FDCPA Federal Jurisdi, civil code 2924, Foreclosure, litigation, Mortgage modification, truth in lending 2923.5

Categories : 2923.5, 2924, Foreclosure, Mortgage modification, Predatory Lending, mortgage meltdown

SB 94 and its interferance with the practice

5 09 2009

CA SB 94 on Lawyers & Loan Modifications Passes Assembly… 62-10

The California Assembly has passed Senate Bill 94, a bill that seeks to protect homeowners from loan modification scammers, but could end up having the unintended consequence of eliminating a homeowner’s ability to retain an attorney to help them save their home from foreclosure.

The bill, which has an “urgency clause” attached to it, now must pass the State Senate, and if passed, could be signed by the Governor on October 11th, and go into effect immediately thereafter.

SB 94’s author is California State Senator Ron Calderon, the Chair of the Senate Banking Committee, which shouldn’t come as much of a surprise to anyone familiar with the bigger picture. Sen. Calderon, while acknowledging that fee-for-service providers can provide valuable services to homeowners at risk of foreclosure, authored SB 94 to ensure that providers of these services are not compensated until the contracted services have been performed.

SB 94 prevents companies, individuals… and even attorneys… from receiving fees or any other form of compensation until after the contracted services have been rendered. The bill will now go to the Democratic controlled Senate where it is expected to pass.

Supporters of the bill say that the state is literally teeming with con artists who take advantage of homeowners desperate to save their homes from foreclosure by charging hefty fees up front and then failing to deliver anything of value in return. They say that by making it illegal to charge up front fees, they will be protecting consumers from being scammed.

While there’s no question that there have been some unscrupulous people that have taken advantage of homeowners in distress, the number of these scammers is unclear. Now that we’ve learned that lenders and servicers have only modified an average of 9% of qualified mortgages under the Obama plan, it’s hard to tell which companies were scamming and which were made to look like scams by the servicers and lenders who failed to live up to their agreement with the federal government.

In fact, ever since it’s come to light that mortgage servicers have been sued hundreds of times, that they continue to violate the HAMP provisions, that they foreclose when they’re not supposed to, charge up front fees for modifications, require homeowners to sign waivers, and so much more, who can be sure who the scammers really are. Bank of America, for example, got the worst grade of any bank on the President’s report card listing, modifying only 4% of the eligible mortgages since the plan began. We’ve given B of A something like $200 billion and they still claim that they’re having a hard time answering the phones over there, so who’s scamming who?

To make matters worse, and in the spirit of Y2K, the media has fanned the flames of irrationality with stories of people losing their homes as a result of someone failing to get their loan modified. The stories go something like this:

We gave them 1,000. They told us to stop making our mortgage payment. They promised us a principal reduction. We didn’t hear from them for months. And then we lost our house.

I am so sure. Can that even happen? I own a house or two. Walk me through how that happened again, because I absolutely guarantee you… no way could those things happen to me and I end up losing my house over it. Not a chance in the world. I’m not saying I couldn’t lose a house, but it sure as heck would take a damn sight more than that to make it happen.

Depending on how you read the language in the bill, it may prevent licensed California attorneys from requiring a retainer in advance of services being rendered, and this could essentially eliminate a homeowner’s ability to hire a lawyer to help save their home.

Supporters, on the other hand, respond that homeowners will still be able to hire attorneys, but that the attorneys will now have to wait until after services have been rendered before being paid for their services. They say that attorneys, just like real estate agents and mortgage brokers, will now only be able to receive compensation after services have been rendered.

But, assuming they’re talking about at the end of the transaction, there are key differences. Real estate agents and mortgage brokers are paid OUT OF ESCROW at the end of a transaction. They don’t send clients a bill for their services after the property is sold.

Homeowners at risk of foreclosure are having trouble paying their bills and for the most part, their credit ratings have suffered as a result. If an attorney were to represent a homeowner seeking a loan modification, and then bill for his or her services after the loan was modified, the attorney would be nothing more than an unsecured creditor of a homeowner who’s only marginally credit worthy at best. If the homeowner didn’t pay the bill, the attorney would have no recourse other than to sue the homeowner in Small Claims Court where they would likely receive small payments over time if lucky.

Extending unsecured credit to homeowners that are already struggling to pay their bills, and then having to sue them in order to collect simply isn’t a business model that attorneys, or anyone else for that matter, are likely to embrace. In fact, the more than 50 California attorneys involved in loan modifications that I contacted to ask about this issue all confirmed that they would not represent homeowners on that basis.

One attorney, who asked not to be identified, said: “Getting a lender or servicer to agree to a loan modification takes months, sometimes six or nine months. If I worked on behalf of homeowners for six or nine months and then didn’t get paid by a number of them, it wouldn’t be very long before I’d have to close my doors. No lawyer is going to do that kind of work without any security and anyone who thinks they will, simply isn’t familiar with what’s involved.”

“I don’t think there’s any question that SB 94 will make it almost impossible for a homeowner to obtain legal representation related to loan modifications,” explained another attorney who also asked not to be identified. “The banks have fought lawyers helping clients through the loan modification process every step of the way, so I’m not surprised they’ve pushed for this legislation to pass.”

Proponents of the legislation recite the all too familiar mantra about there being so many scammers out there that the state has no choice but to move to shut down any one offering to help homeowners secure loan modifications that charges a fee for the services. They point out that consumers can just call their banks directly, or that there are nonprofit organizations throughout the state that can help homeowners with loan modifications.

While the latter is certainly true, it’s only further evidence that there exists a group of people in positions of influence that are unfamiliar , or at the very least not adequately familiar with obtaining a loan modification through a nonprofit organization, and they’ve certainly never tried calling a bank directly.

The fact that there are nonprofit housing counselors available, and the degree to which they may or may not be able to assist a given homeowner, is irrelevant. Homeowners are well aware of the nonprofit options available. They are also aware that they can call their banks directly. From the President of the United States and and U.S. Attorney General to the community newspapers found in every small town in America, homeowners have heard the fairy tales about about these options, and they’ve tried them… over and over again, often times for many months. When they didn’t get the desired results, they hired a firm to help them.